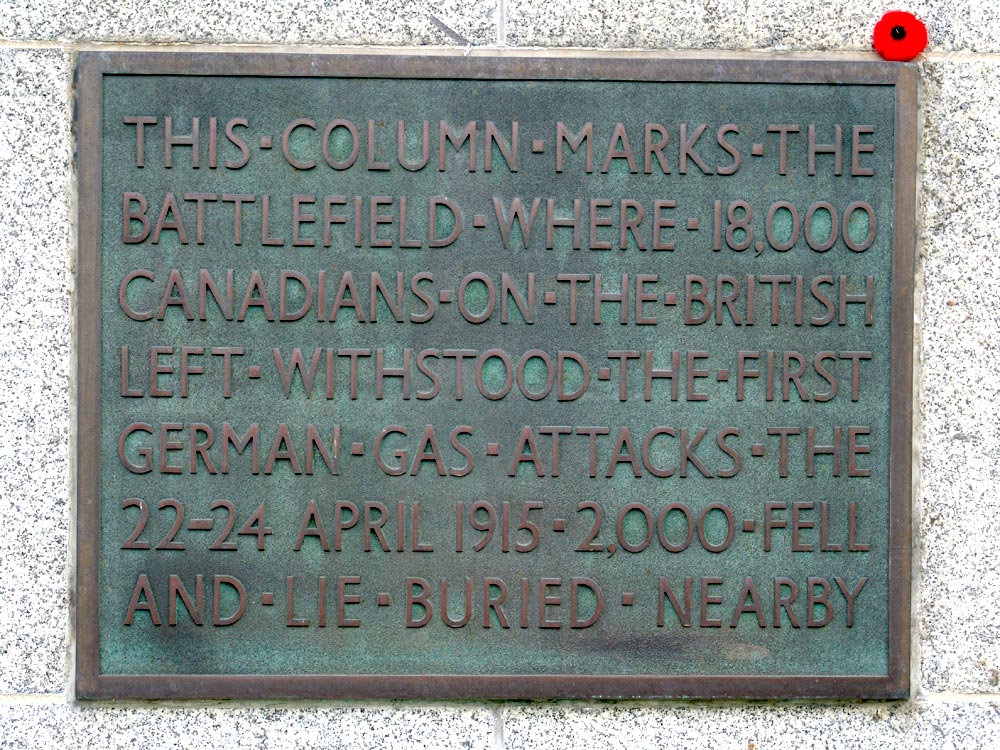

Battlefield: The Battle for Ypres

In April 1915, the Ypres Salient in Belgium had become the most dangerous and violent spot on earth

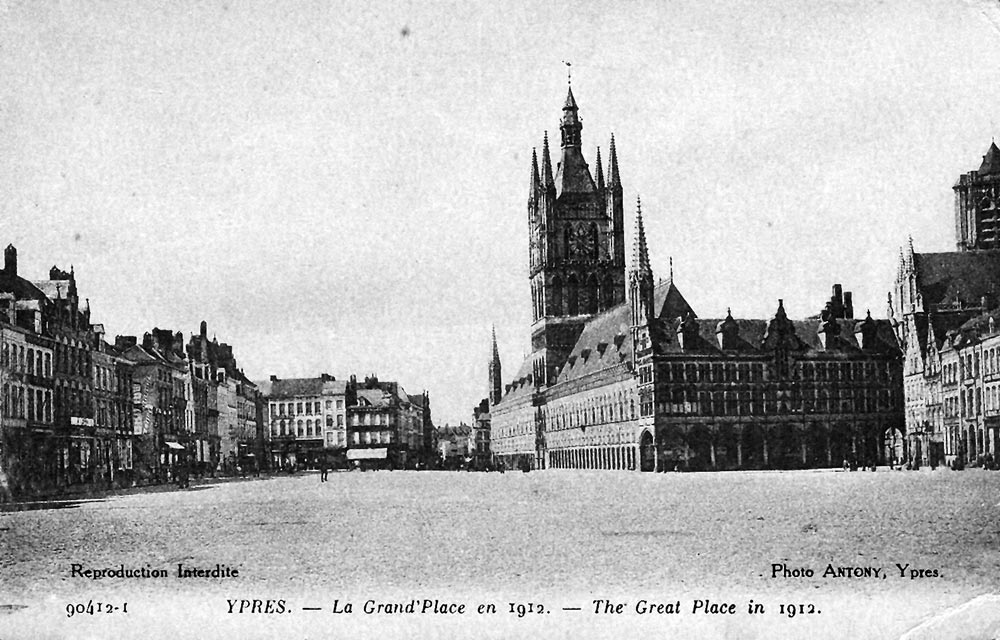

Ypres 1912

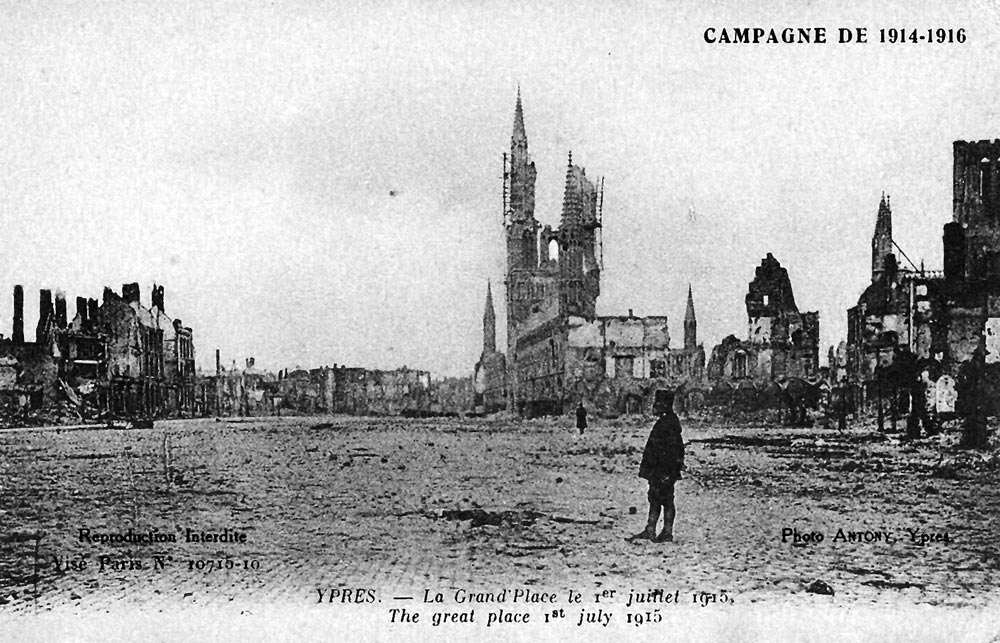

Ypres 1916

The first Canadian Contingent arrived in Plymouth, England in mid-October, 1914. They were moved to a tent-camp on the Salisbury Plain, in the south of England, near Stonehenge. The British had not been prepared for the arrival of so many Canadians.

The 20,000 men of the 1st Canadian Division crossed the English Channel and disembarked at St. Nazaire on the French coast in February 1915. After several days of confusion, they were finally marched to a new camp where they waited for their equipment to arrive and did some light training.

Their first taste of war came when they entered the trenches in a quiet sector, near Fluerbaix, on the French-Belgian border. At Fluerbaix, they were introduced to trench warfare, the mud, the rats, and the constant fear of sudden death by snipers, trench mortars or artillery. It was at Fleurbaix that the first Canadians died, mostly shot through the head by expert German snipers or killed by shrapnel released in the overhead explosions of artillery shells. By First World War standards, this trench ‘wastage’ was insignificant.

In April 1915, the 1st Canadian Division received orders to leave the Fleurbaix sector and move into the trench-line northeast of the ancient Belgian city of Ypres. It was at Ypres that the Germans had tried to crack the British line in the fall of 1914. Attacking in swarms, they were shot down by rapid rifle fire of the British troops. The bodies of German, British and French soldiers killed in 1914 still lay where they had fallen, rotting in the spring sun. The odour of decaying flesh, which became synonymous with the Ypres area, mixed with the sweet spring air.

The desperate fighting in 1914 had produced a bulge or salient in the British line west of Ypres that protruded into the German-held territoy, and this bulge allowed the Germans to attack from both the front and the back.

April 22nd, 5:00pm : Gas Attack

It was a beautiful spring day; warm, fresh sun and a westerly breeze blowing towards the Allied lines. The German shelling intensified and the bombardment became furious. The Germans opened the valves of the 5,500 gas cylinders that had been buried in their trenches and the westerly wind swept the gas forward. In front of the French Colonials, two large, curious yellow clouds rolled out of the German lines, joined up, and started floating towards them. There was an odd smell in the air and eyes suddenly became itchy. The gas attack had begun.

The Canadians adjacent to the French were not in immediate danger because the westerly wind was propelling the gas north of their positions and into the French lines. The huge cloud of gas, one kilometre thick and 700 metres wide, was moving at a speed of about 8 kilometres and hour. As the Canadians watched the yellow gas billowing forward, they could see the French deserting their positions and running back towards Ypres. In their wake, they left a gaping hole about 12 kilometres wide on the left flank of the Canadians.

The Germans waited for the gas to disperse and moved into the newly opened French lines, but by now the Canadians had been ordered to fill the open flank. The 13th Battalion from Montreal, the kilted Royal Higlanders of Canada, were the first to engage the Germans. At first the Germans moved away but were finally forced into confronting the Montrealers. In a short, vicious fight, Guy Drummond and his men were overwhelmed. Their sacrifice, however, was critical to the final outcome of the battle. By stopping the Germans from coming behind the Canadian lines, they had prevented the 1st Canadian Division from being surrounded and they had deflected the main onslaught of the German attack northward.

Ypres Today